The NZ Government has suggested that we should make ourselves carbon neutral by planting many millions of additional forest trees. If this is to become a reality there will be a need for new nurseries to be established to cater for the many millions of trees that will be needed.

So, now is an opportune time to remind ourselves of the need for these nurseries to ensure that their plants are well infected with the correct mycorrhizal fungi. This is particularly important if the trees are ectomycorrhizal species, for example pines, Douglas fir, and eucalypts, and are to be planted into cropping areas, grassland and scrubland where there are unlikely to be any ectomycorrhizal fungi present.

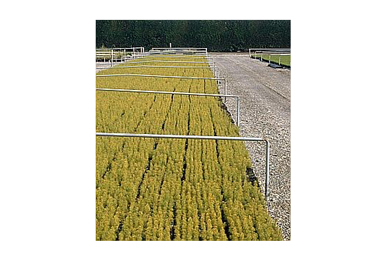

Some of you will remember the problems that were encountered in the 1980s when some nurseries failed to do this and Douglas fir planted into upland areas of Southland, Otago and Canterbury turned yellow and died. A recent chapter in a book “Commercial Inoculation of Pseudotsuga with an Ectomycorrhizal Fungus and its Consequences” written by Ian Hall, Chris Perley and colleagues reminds us of the potential problems. The chapter outlines how a new nursery established in North Otago in the mid-1990s, which was capable of producing about 10 million containerised trees, was faced with a sea of yellow Douglas fir seedlings (photo).

Preliminary studies by Ian Hall and his truffle team showed that none of the trees had any mycorrhizal fungi on their roots. In an attempt to get a quick fix, the nursery had heaped on nutrients to try to correct the problem. It turned out this was the worst thing they could have done because it made the plants unattractive to mycorrhizal fungi. If these had then been outplanted into the upland runout pasture in Southland where the plants were destined for and where there were no sources of suitable ectomycorrhizal fungi, the trees would probably have grown a little then turned yellow, become stunted and died.

So, a suitable mycorrhizal fungus was selected (Rhizopogon parksii) which was relatively easy to manipulate, a method developed for quickly inoculating all the seedlings, and providing not too much fertiliser was applied in the nursery, it was possible to ensure that the millions of seedlings were mycorrhizal, suitable for outplanting and guarantee good growth. The plantation at Gowan Hills is now more than 20 years old, the stand is even and there is no sign of yellowing.

In the discussion of the chapter the authors then delve into the vexed question regarding the replacement of our iconic grasslands with trees in those areas where forest would have covered the land before the arrival of man. They also suggest that it would have been better if the Douglas fir had been mycorrhized with fungi that produced edible mushrooms although at the time this was not an option – the forestry company simply couldn’t wait for the development of the additional technology.

However, this has now been developed so that radiata pine, Scots pine, and stone pine can be mycorrhized with the delicious saffron milk cap mushroom. Indeed, the stone pine offers the possibility of triple cropping a stand – mushrooms after a couple of years, then pine nuts and finally timber, an option that Ian and his colleagues have been working on in New Zealand, China and elsewhere for more than a decade. With a little more work, it should also be possible to inoculate Douglas fir with one of the edible North American truffles or Suillus lakei (painted bolete).

A copy of a conference paper given by Ian Hall in China last year on the production of edible mushrooms as secondary crops in plantation forests can be downloaded from Research Gate.

Source: Truffles and Mushrooms (Consulting), www.trufflesandmushrooms.co.nz