OPINION: Billion Trees will fail without Wood First policy

(Marty Verry is CEO of Red Stag group, which operates the Southern Hemisphere’s largest sawmill and has investments in over 3,000 ha of forestry, a pre-fabrication plant and property developments.)

Would you invest $481 million in growing a product on the assumption that the price and demand for it in China in 28 years will be the same as it is now? Of course not. But you are. We all are through the Billion Trees programme.

China takes seventy-five percent of New Zealand’s logs. You could say we have all our logs in one basket. So the question nobody has asked is, will the demand for our trees be there in twenty-eight years and at what price?

Tens of thousands of hectares of farmland has been snapped up by investors, giddy with grants from the $481 million Provincial Growth Fund allocation to the Billion Trees programme. They have pushed land prices up forty-five percent according to the Real Estate Institute of New Zealand.

Farming communities are up in arms at the rapid change, and rightly so in my view. No so much because trees are bad (they are great), but because many of these forests could become investment failures, never to be harvested, and a fire and forest disease risk for decades. A white elephant in every rural road.

So why the doomsday scenario, and what can be done about it? -Firstly, a reality check on relying on China long term for our billion trees. Despite MPI targeting having two-thirds of its 50,000 hectares extra planting annually going into natives, the Billion Tree cabinet paper acknowledges most will be in plantation crops requiring harvesting and re-planting. This seems right given MPI’s own CO2 sequestration look-up tables show natives only absorb one tonne CO2 per hectare annually after fifty years. Hardly a long-term solution to climate change, and certainly not a great return for investors.

What about manuka honey? Manuka is a nursery crop for the larger natives that will eventually take over. So no long term putea for the mokopuna, as the forestry minister might describe the lack of money for the grandkids.

No, the majority of the billion trees will be radiata pine, and radiata pine needs harvesting and re-planting to make the feasibility models work and keep forests healthy. That relies on demand and pricing that covers the cost of land, planting, silviculture, harvesting and transporting the logs.

The problem arises because we are not the only country to work out trees sequester CO2, and launch a billion tree policy. There are a plethora of them around the world. India has planted a billion trees. So has Ethiopia. Pakistan has a ‘Billion Tree Tsunami’ programme underway. A UN billion tree campaign was so successful it was upgraded to a Trillion Tree programme. Even Australia has a billion tree policy.

So, will China need our one billion trees? Ten years ago it temporarily stopped harvesting to replenish its own forest estate. New Zealand’s supply shot up to forty-three percent of China’s log imports. However, it recently announced plans to increase its own forestry estate by 11 billion cubic meters by 2050. China could be producing enough of its own wood products to replace log imports from New Zealand six times over.

This is before one factors in the huge increase in supply targeting China from the rest of world and New Zealand’s own increased production, and the fact that the demand now from China is largely driven by the huge urbanisation programme underway there which will be largely complete by the time our billion trees mature.

This supply-demand imbalance is already playing out in China. Log prices there have crashed by fifteen percent in the last month on the back of huge volumes of cheap wood from Russia and Europe being back-loaded cheaply on trains that would otherwise return empty to China. The Silk Road project will make it easier still. At wharf gate returns are reportedly off up to $29/tonne locally, with logging crews reportedly being laid off as foresters can’t justify harvesting.

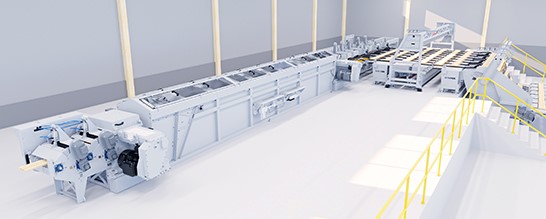

This is the market reality for our Billion Trees unless New Zealand can widen its markets and demand for wood products. Wood dominates in lower-rise housing in most countries, so the big opportunity is in the market for mid-rise buildings. New mass timber products such as cross laminated timber (CLT) and glulam are the enablers here.

Governments around the world have recognised the key leadership role they can take in this area, given they are typically the largest procurers of buildings in any country. Many have adopted ‘wood first’ policies for their own building procurement.

In its 2017 Election Manifesto, the Labour Party promised if elected that it would require that “all government-funded project proposals for new buildings up to four storeys high shall require a build-in-wood option at the initial concept / request-for-proposals stage. … Due to advances in engineering and wood processing technologies, we will increase the four story requirement to 10 stories.”

Research conducted for this policy established it could lead to a doubling of demand for structural timber in New Zealand.

Without it, planting one billion trees targeting China risks almost certain failure – either for the government achieving its policy goal, or ultimately for the investors holding white elephant forests.

The Wood First policy has strong broader rationale for adoption, including regional jobs and manufacturing, faster build times, cheaper, safer, less polluting construction, and the displacement of mainly imported steel and concrete which each account for around five percent of climate change emissions.

The folly of having all our logs in the China basket is becoming apparent. To date, the government has failed to implement its promised Wood First policy. What credibility does New Zealand have in international climate change accords if it fails to implement its domestic pledges?